Forty years after I had last travelled to Lo Wu, the electric line from Kowloon ran from a new and relocated station no longer allied to the Star Ferry landing. Long gone were steam trains and open trucks for Chinese on the lowest fares; all – not just the British and more prosperous Chinese – now sat in comfort in coaches. Of the former stations, only Taipo Market had been preserved – a quarter mile from a large new station where the restaurant served spaghetti bolognaise – and no chopsticks. No longer were women at the old stations selling strips of dried beef and chiclets from trays and handed through open carriage windows; the now electrified line and its architecture came all from an international rapid-transit model design manual. Nor was there any graffiti – utterly unlike the Paris RER, the New York subway or – increasingly – the London Underground.

The New Territories of predominantly paddyfields were now superimposed with highways, new towns, building sites, power lines, quarries, scrapyards and abandoned rural roads. Rice paddies now planted for vegetables, but Hakka women still planting and harvesting with their round disc hats rimmed with a black curtain ad a handkerchief covering their exposed crowns. As I walked at Hakku Wai, the old women at the gate of the handsome walled village – like a Flemish beguinage – chattered irritatedly when they saw me pass and moved beyond sight; the open door to the village shut without a hand being shown.

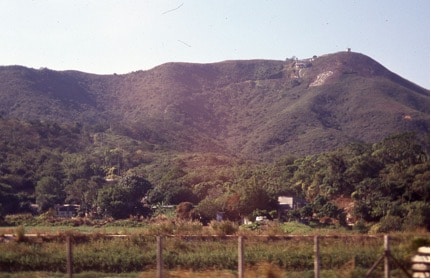

Crest Hill, Lo Wu 1990

Lo Wu had significantly changed. Although Hong Kong and the New Territories remained under British administration until 1997, the camp which the Royal Artillery had occupied in 1950 had now been succeeded by a detention centre for Vietnamese boat people who had escaped by sea to Hong Kong. From behind the barbed wire surrounding fence, screams and shouts came which were far less controlled than any of even an army camp.

I would have wished to climb Crest Hill again to look out over the great new city of Shenzhen prior to visiting over the border the next day. Warning signs of the Closed Zone and of a firing range dissuaded me. I chose not to be shot close to the Chinese border in 1990, having been at less risk of that fate as a soldier forty years before. The following day – with a visa readily obtained in Kowloon – I took the train to the border station of Lo Wu. I made the crossing into the People’s Republic impossible for me in 1950. Met by a Chinese Planner kindly arranged for me by a Chinese student of my department in Glasgow, I was given a day trip around the new urban landscape, wholly grown up in the decade since 1980 and forty years since my time at Lo Wu. A circle was closed on my experiences of National Service.

Leave a Reply