We were ready to take the second class trade test, which would take place back in the UK at Larkhill. We were told that only one re-sit would be allowed and no extra pay until after two years. As no one wanted to sign on for three years, by midday all except a couple of regulars failed and we were given warrants, ration cards and told to go home and report to Liverpool Street station a week later for return to Germany.

Goodge Street Deep Shelter

Not being satisfied with a week’s leave, Len Lynch who had been at Erith Technical college with me and remained with me through National Service, contrived to keep getting to the back of the queue for the train until the train was full. [Read more…]

Our Final Leave and Final Thoughts

A final fourteen day leave was permitted in the UK or slightly longer at a rest area in The Harz Mountains – Who was foolish enough to turn down a free skiing holiday? [Read more…]

Wannop – Park Hall Camp, Oswestry

The National Service Act of 1948 which came into force on January 1 1949 obliged all young men reaching the age of 18 – and passed fit – to serve for 18 months in one of the armed forces. Most of my classmates at school chose the available option of deferring call-up until after university, but I preferred to go for service first. When an announcement at morning assembly offered those who by accident of birthday date could enter service before reaching 18 and thereby delay university for only one rather than two years, I accepted the offer. Passed fit in the medical examination, I recall no choice of service to join, but left school at the end of the Easter term 1949 on an Order to join the 17 Training Regiment of the Royal Artillery at Oswestry on 7 April, as one of National Service entry group 4907.

Provided with a rail travel warrant, I arrived in North Wales with other young recruits after an overnight rail journey from the old Caledonian station in Edinburgh. Worn, grubby and tired after sitting upon a sleepless overnight journey, we were shouted at for the first time as herded at Gobowen Station into trucks to carry us to our initial weeks of training and sifting at Park Hall Camp. Cut to the scalp by military barbers, issued with kit and my army number of 22127006 which over 70 years later is instantly recalled and more readily memorable than current car registration or cash machine PIN numbers, it was a hard day after a sleepless night. Exhausted, we were pliable as the army wished us to be.

The following fortnight of indoctrination, intelligence and other tests and collective bullying was much alleviated for the Scottish recruits when – on the initial weekend confined to barracks to polish new brasses, to blanco new webbing and to attempt to shine the toes of ugly black boots – the Tannoy speaker system in the huts brought commentary on Scotland’s victory over England at Wembley in the then annual football international. In the next weeks, as screaming and insults descended on the parade ground from raw young lance bombardiers with only a few months service of their own, we could look them in them eye and in the afterglow of Scotland’s success deflect their exaggerated abuse adopted to beat us into obedient shape.

In the programme of intelligence and aptitude tests filtering us into streams useful to the Artillery, it was a surprise to learn that national servicemen might receive officer training. An invitation to apply for selection came, but following instruction to write an essay on ‘Adventure’ and subsequent interviews with a senior officer, a gap could be seen between official expectations and those of we frequently reluctant conscripts. Some colleagues chose to go ahead to further tests of their ambitions of command and of officer selection, but several declined. Some might have observed an impossible gap between the events and aftermath of the war ending scarcely four years before and the idea of service life as an opportunity for ‘Adventure’. Others’ brief experience of National Service was already enough to have seen evidence of the environment of army attitudes towards youthful national service officers, ranging thorough disdain from experienced officers, contempt from regular gunners including veterans with wartime experience, on to amusement and generous pity from long service sergeants.

An early introduction to army inefficiency came when our indoctrination as artillerymen continued by visiting the Trawsfynydd firing ranges. After an overnight in Nissen huts on a sodden, rainy hillside, the morning came with the realisation by those responsible that they had brought no fuses that were essential to firing the 25 pounder guns. Only subsequently at summer camp with my territorial unit on Salisbury Plain did I experience the Royal Artillery’s principal purpose of delivering shells, rather than of locating their sources in enemy lines as I would be trained to do.

Wet and abortive weekends in Wales were to mark both the beginning and end of my service, as I found out some seventeen months after the Trawsfynydd fiasco when I again made a fruitless trip to the Principality.

Wannop – Larkhill, Salisbury Plain

After the initial weeks of introduction to army life by hard discipline, barrack square drill, less than tasty food and aptitude testing, I was posted to the artillery survey training school at Larkhill at the far western edge of the military camps on Salisbury Plain. Our group were presumably selected by aptitudes for mathematics and geography, chosen to undertake six months of training as artillery surveyors leading into one of the army’s then more esoteric branches. We were to locate enemy guns, not to fire any of our own directly.

Billeted in wooden huts with cast iron stoves to counter the winter cold of the Plain, our diet was of prunes for breakfast and slabs of meat for supper. When the orderly officer came around and asked if the meals were satisfactory, he did not expect to be given a true opinion and none was offered.

More enjoyable were trips in trucks around the countryside for reasons which I cannot remember, when benevolent sergeants took us to enjoy cream donuts at country pubs. At the weekend we could go into Salisbury to enjoy the open Saturday market – unfamiliar to a Scot – or walk over the flood plain of the Avon and look back to the Cathedral spire which almost split the sky.

It was a warm and dry summer on the Plain, and I recall walking from the camp one quiet evening down a flint and chalk track to Stonehenge, then completely open to passers-by and under no protection from casual visitors.

There were other enjoyments at Larkhill. One avuncular sergeant captained and was goalkeeper to the unit hockey team. The team primarily comprised national servicemen but included one officer in the only marginal social mixing of non-commissioned and commissioned ranks I experienced in the year and a half of my service. Pitches at the various camps at which we played on the Plain were superb – engineered by the army from chalk, planed as flat, firm and as green as billiard tables. One particular memory is of our goalkeeping sergeant leaping in the air, waving his hockey stick in delight as his transient team of young soldiers scored the equalising goal against a unit apparently only recently champions of the Middle East army command. This was great status for our captain to earn amongst other hockey playing units on the Plain.

A periodic and unwanted responsibility was guard duty, carrying not arms or ammunition but pick shaft handles, wandering in the dark around the buildings of the survey school and on the heathland surrounding the camp. Two hours perambulating and then four hours off, resting as best could be achieved on the unforgiving wire base of the beds. Tired feet remained in heavy boots until the next of the two, two hour shifts which all served in the night.

Returning from a day trip to London with a T shirt which at the time was an unfamiliar sight in Britain, was the cause of my only experience of the traditional army punishment of cookhouse duty. A lance-bombardier seeking a victim for the cookhouse to peel potatoes, ignorant of the arrival from America of Tee shirts to become a ubiquitous mode of British dress, spotted me playing basketball outdoors one Saturday afternoon. Assuming that I was wearing an undervest in public, I was sent as punishment to peel potatoes for the rest of the afternoon.

On working weekdays we trained in the huts in artillery survey techniques of flash spotting and sound ranging, employing our school education in geometry and trigonometry, but we were also introduced to Lee Enfield .303 rifles which had been the British infantry’s staple since the Boer War and through two World Wars. Expeditions onto the Plain reminded us that soldiers had wider purposes than the application of mathematics; we took our issued .303 rifles for experience on the ranges, firing Sten and Bren guns with trepidation. I recall an overnight exercise on the Plain, which added to the passing contact we had with more common military practice. Never again in my service did I fire a shot in either anger or by way of training.

Qualifying in October as artillery surveyors, my group’s posting was initially to Woolwich Barracks in London and then home for pre-embarkation leave for sailing to Hong Kong. Our expected days of leave at home were unhappily curtailed after 5 days when telegrams recalled us to Woolwich; the Devonshire, our troopship for Hong Kong, had been lodged for repairs in a Merseyside dock and its sailing was being further delayed. Returned from Woolwich back to Larkhill, we lodged there for six weeks until given an unexpected fortnight’s leave for Christmas and New Year. Returning after that for a week at Woolwich in early January, our state of limbo was alleviated by our being sent for yet another four days of leave, followed by another week at Woolwich, living and sleeping in barrack rooms at first floor level opening onto a wide balcony projecting above the parade square below. Our predecessors from the days of horse drawn artillery would have brought their horses up from the stables below for currying and exercise on the balcony.

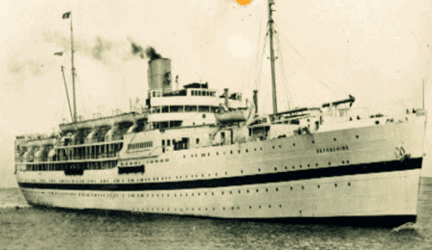

Filling out the waiting time at Woolwich with compulsory runs in Greenwich Park, we finally travelled to Liverpool to board the repaired but rusty old tub of a troopship, the Devonshire, moored at the far and very forlorn end of the Birkenhead docks. The next day we wove a passage out to cross the Mersey to the Liverpool Pierhead, from which so many before us had emigrated either willingly or reluctantly to North America and Australasia. Loading more servicemen for the voyage, after almost three months in limbo we were finally ready for a six week passage to Hong Kong.

Wannop – To Hong Kong on the Devonshire

We sailed east on the 24 January 1950 from the Pierhead, from which emigrants had shipped west to North America fifty years before. Launched on the Clyde just ten years previously and fitted out as a troopship, conditions on the Devonshire seemed to us perhaps scarcely better than for those fifty years before sailing as emigrants to North America. Meals in bulk had to be carried down in containers from the galleys to the deck level where we lived, ate and slept. The food was no treat to receive; on the mess tables cleared of papers and clothing for meals we were presented with unappetising food of which pilchards in cold tomato sauce were particularly unappetising and wholly unsuited to anyone inexperienced in the rolling waves of the Bay of Biscay. Later on the voyage, however, oranges brought up from cold store were a rare pleasure after the barren days of food rationing still lingering in the UK.

Winter in the Bay of Biscay and even through the Mediterranean was not a season in which to much enjoy the shoreline landscape of Spain, or later of the Red Sea. It was possible, however, to go forward on the open deck to watch dolphins leap from the water and plunge ahead of the bow as it cut the water. Flying fish would follow the lead of the dolphins, darting above them at speed.

Our first direct contact with foreign parts came when briefly anchoring at Suez, when Egyptian traders paddled out in bumboats to sell sweets and souvenirs. Baskets on a rope were hauled up with the goods desired and returned back with money to the traders in the craft below. After sailing through the Suez Canal, the first shore leave came at Aden on Feb 8, bringing for most of us the first experience of placing foot on foreign soil. This all at a time before the days of mass flying to foreign holidays in the Mediterranean, the Maldives or other places then barely accessible except by sea. More brief release ashore came at Colombo a week later, followed by Singapore after passage through the Straits of Malacca. Hong Kong followed after a further five days through the South China Sea, completing a voyage from Liverpool of five weeks. There is still a picture in my mind of turning close around the rocky coast towards Hong Kong Bay. We moored by the Kowloon godowns, disembarking to board a steam train at the then Kowloon station, since displaced. We British troops had compartmented carriages to sit in, but many Chinese huddled in open trucks at the rear of the train. At the stations on the line, vendors brought trays of chewing gum and cuts of dried meat of origins unrecognisable to us.

The line to Canton being than closed at Lo Wu at the border with the new People’s Republic, the last open station on the line was Sheung Shui, from which we were trucked to the camp at Lo Wu where I spent most of the next six months. The almost wholly tented camp lay in the lee of Crest Hill in the line of hills separating us from the People’s Republic, declared by Mao in Beijing just four months before. My unit was the 15 Observation Battery; associated in residence in the camp with the 173 Locating Battery of the Royal Artillery.

Wannop – On the Frontier: Lo Wu Camp

Emerging from our tents at Lo Wu for our first morning parade on Feb. 27 1950, our welcome to China was by a lone Nationalist bomber of US origin flying in over the New Territories over our heads, dropping bombs over the border on the Chinese side in the vicinity of the railway line, close to a barracks of the People’s Republic Army. Its brief gesture over, the aircraft turned immediately to escape back to Formosa before the arrival of a flight of Spitfires from Kai Tak. For many years I thought that this might have been the last assault by the Kuomintang on mainland China – from which they had been largely expelled, only long after learning that three weeks later the Nationalists made a late fling in its long war with Mao and what had become the People’s Army, landing a force on the mainland coast north towards Shanghai.

South of Hong Kong, also in March, the People’s Army landed in greater force on the island of Hainan, driving out the occupying Nationalist troops by May. Nothing of the impact of these incursions was felt by us at Lo Wu, nor do I recall even learning that they had occurred. I have no memory any official briefing giving information about our position or that of Hong Kong in the changing Chinese world. Hong Kong’s security from any invasion across the border was in little doubt, because it was to the Chinese advantage to see out the life of the treaty legitimising British tenure of the New Territories. However, I had no fear of or expectation of any incursion by the People’s Army, although its troops were in view of our binoculars when we took observation duty from the top of our adjoining Crest Hill.

First morning on parade at Lo Wu, February 27 1950. Bomb strike by Kuomintang aircraft on Peoples’ Republic side of border.

Lo Wu Camp 1950

Within the camp at Lo Wu there was a NAAFI hut and Chinese pedlars who came with unfamiliar confections like American Babe Ruth toffee bars. A Chinese concert party visited for one evening performance, but there were few other and only minor pleasures. No opportunity to again play hockey, but relief from the high humidity could be had by dipping in a storm balancing tank. Of an evening, we could stroll closer to the frontier and with villagers exchange a few grubby Hong Kong five or ten cent notes for souvenir currency of the Peoples’ Republic. There was no pleasure in a sweating climb up the zigzag path on Crest Hill for occasional overnight duty at the observation post overlooking China proper. Up the path, we carried full, top heavy jerry cans of water on frames on our backs, risking tumbling off the path as the weight of the water shifted in its container.

From the post itself, an ocean of paddy fields stretched to a line of hills on the horizon. Across this wide foreground of cultivated landscape ran the rail line from Kowloon to what then still known as Canton, far out of sight beyond a wall of hills paralleling that on which we stood in the New Territories. Then, no rail traffic crossed from the New Territories over the frontier, nor was there any complex of customs and visa control as I crossed through forty years later. The principal interest seen through field glasses was soldiers of the People’s Army sitting on the doorstep of their barracks by the rail line, perhaps the target of the bomber from Formosa of our first morning on parade at the Lo Wu camp.

We were innocent then of any foresight that the ocean of paddy fields before us would after 1980 be replaced by an industrial metropolis reaching an estimated population of 15 million within 30 years, outstripping the population and economic growth of Hong Kong and the New Territories. The Special Economic Zone established by metropolitan Shenzhen has become effectively the largest new town or city ever planned and built, more populous and larger in economic activity than achieved by all the new towns of the UK together in twice the lifetime. On my first subsequent visit to Hong Kong forty years later, it was fascinating for one who had come to a career as a town and regional planner – including a major period working on new towns in the UK – to return to a remembered landscape of paddy fields now overcome by the special economic zone of Shenzhen.

Guard duty at Lo Wu was ambling in the dark with rifles rather than the pickaxe handles of Larkhill, but not with matching ammunition. As we patrolled in the dark on two hour shifts, the night was heavy with the croaking of frogs from the paddy fields beyond the bamboos on the camp’s edge. In the still, humid and heavy night air, luminous caterpillars shone in the dark and trodden underfoot left a smear of fire.

Gunner Urlan Wannop, Lo Wu 1950

L to R. Gunners Pearson, Wallace and Wannop prior to guard duty Lo Wu 1950

Wannop – Lo Wu Camp Diversions – Hong Kong

Off duty on Saturdays, we could choose to take the train or be trucked to Kowloon for an afternoon and early evening out in Hong Kong or Kowloon. When by train, we would reach the station at Sheung Shui by walking and balancing on the low narrow turf walls dividing the paddy fields, in which Hakka women might be spreading night soil from buckets hung from yokes across their shoulders.

With still remaining elements of wartime rationing left behind in the UK, it was a treat to enjoy a British mixed grill at the servicemens’ club on the Victoria Island shore of Hong Kong to sampling Chinese food, entirely unfamiliar before the arrival to the UK in the 1960’s of restaurants serving exotic food from the Indian sub-continent and the Far East. Stalls in Hong Kong alleyways gave off the heavy scent of duck fat, inducing queasiness and not a pleasing anticipation as now arises with experience and very pleasurable on visits to China and Malaysia years later. Culinary experimentation was uncommon and rarely sought by young servicemen. There was then no extensive background of Chinese restaurants in the UK except in London and Liverpool, and only one in all Edinburgh and that with a doubtful although probably unfair reputation.

On the slopes of the hills above Kowloon was a tumble of shacks built by Chinese who after the Japanese retreat had crossed the border from China proper, rebuilding the colony’s population fallen to as few as 500,000 during the Japanese occupation, but trebling in the five years following. Most structures seemed little more substantial than packing cases. The colony’s administration appeared relaxed as Chinese came over the border from the new People’s Republic. Reporting swimmers coming across the border river when on duty at the observation post on Crest Hill, Hong Kong Police arrived but seemed little interested and with no intent to take the incursion as of any seriousness.

A fortuitous and pleasant break for me from military duties came with a week on leave to the Servicemen’s Club in Victoria on Hong Kong Island. The week was won by rare success from a raffle amongst all members of the unit at Lo Wu. The week allowed me not only the pleasure of eating better than at the camp, but it allowed exploration of Hong Kong at more leisure than allowed on fleeting trips on Saturdays.

Rising up the Peak on Victoria Island by the old funicular railway, the summit was then still wholly accessible and uncluttered with today’s telecommunication masts. The summit then gave a wide view of the great scattered array of junks, steamships, occasional warships and the Kowloon ferry on the great Bay below. A memorable day of the week was taking a journey across the island to Repulse Bay to swim in water of absolute clarity; looking down perhaps 18ft to sand below, I have never before or since had such an experience of seemingly floating and swimming in air rather than water.

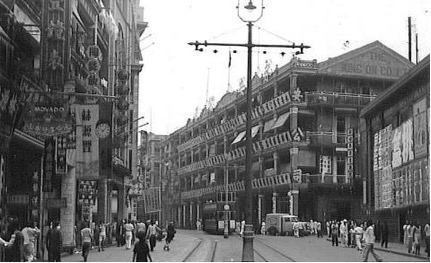

Des Voeux Road, Victoria, Hong Kong. 1950’s

Des Voeux Road, Victoria, Hong Kong. 1950’s

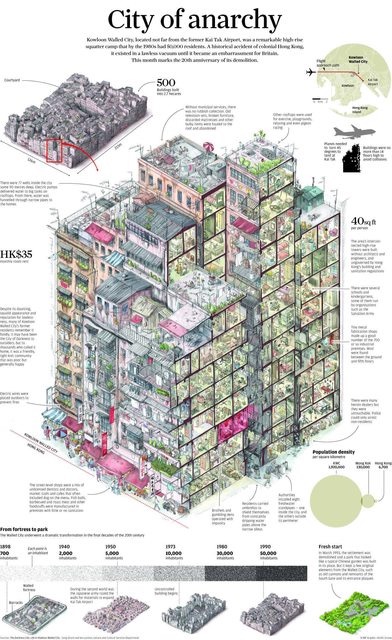

Wannop – Kowloon the Walled City

Of old Hong Kong, the Walled City in Kowloon was Out of Bounds to British servicemen as effectively it was to the British authorities. Then still of traditional compound form behind its walls, it had barely begun its subsequent forty year intake of people and rise to the height of a dozen or so close packed storeys of superimposed, crudely constructed dwellings. Returning to Hong Kong in 1990 for the first time since 1950, unrestrained by army uniform or regulation, I was able to walk through the only remaining quarter of the fascinating slum that had grown up but was now in course of complete demolition, to give way to a public park. The remaining quarter of this 20th. century city was more like medieval Edinburgh than like the tower dwellings of the rest of Kowloon as developed since 1950. Served not as the Edinburgh of the 16th. Century had been by wells, running water was piped but much of which seemed to leak and drip from broken pipes above the alleys, all amongst a tangle of trailing electric and telephone wires probably illegally tapping into mains supplies.

Kowloon Walled City; after 1950

Wannop – A Prelude to Demobilization

Prior to a brief placement in barracks on the Victoria side of Hong Kong Bay for a few days before embarking for shipment back to Britain, we left Lo Wu for a short spell. We were based in a house in a camp where we played basketball amongst lychee trees. One rest day, a bottle of American rye whisky shared out by a colleague on a hot afternoon induced an afternoon of deep slumber and – for I at least – a lifelong distaste for whisky and its consequences.

What contact had we with any Chinese culture? Little, I think. We had come from a Britain which had then little experience of Chinese food except in small pockets in London or Liverpool. Wartime rationing remained in parts of the British diet which were unrestrained in the service retreats in Hong Kong, where we ate what had been limited at home for the past ten years of our upbringing. The sweet scent of duck fat from the alleys on Victoria Island and in Kowloon was sickly and unappetizing. I cannot recall trying any local Chinese food, not on days out in Kowloon or on Hong Kong island, nor at halts on the railway to Sheung Shui from vendors who came to the carriage windows with trays offering cuts of dried pork, duck and possibly other unrecognized meats.

Wannop – Return to Southampton via Empire Fowey

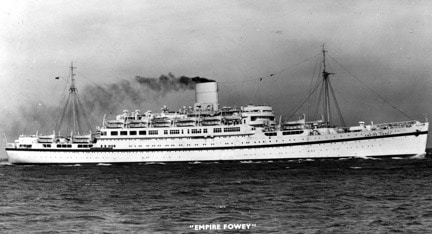

North Korean troops had invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950, however, the potential implications of the war did not impinge on those of us due to return to Britain for release from National Service. Together with fellow conscripts with whom I had trained from Oswestry and on Salisbury Plain through the summer of 1949, I embarked on the Empire Fowey in late August to return to Southampton and the UK for demobilization.

We sailed only shortly before it was agreed that Britain would join the United Nations forces in Korea. The Middlesex Regiment was advised on 23 August of their to move north, sailing to Pusan two days later. The 15 Observation Battery in Hong Kong was retitled as the 15 Locating Battery before it also moved to Korea in December 1950.

Shortly into our voyage of four weeks came the Parliamentary announcement on 12 September that an extra six months service would be added to my entry group of early April 1949; all subsequently engaged National Servicemen were to serve a full two years. An addendum to the announcement conceded that the extra six months would be waived for those due to start university in October, which released me as one of the relatively few National Servicemen serving for only 18 months. Colleagues returning to Britain who had joined with me at Oswestry on the same day in April 1949, and with whom I had since shared Salisbury Plain and my time in Hong Kong remained in uniform, undertaking time-killing trivial duties until their later freedom.

Empire Fowey

The Empire Fowey was a former German troopship taken over at the end of the War in 1945, providing a much more comfortable trip than that out to Hong Kong. Although an older vessel than the Devonshire and built in Germany, the living environment on the Empire Fowey was much superior to that of our outward passage six months earlier. There was relative comfort in sleeping with fold-down standees in place of hammocks; meals were eaten in canteen space, not on the deck where lived and slept. Assigned to work washing trays in the steam sodden galley brought out on me on an outbreak of prickly heat, persisting into early years of civilian life and coming to the surface customarily, curiously and particularly in Binn’s department store in Edinburgh.

Another memory is of a film show on a starry evening on the open deck passing through the South China Sea; bizarrely, we were watching ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ as we lounged on deck on the warm tropical evening.

Wannop – Demobilisation

Disembarking at Southampton I was issued a rail warrant to travel to Edinburgh, to be housed for my last week of full-time service with the Artillery unit closest to that of the Territorials with which I would serve my three obligatory post service years of an annual fortnight’s camp and three weekend exercises. My posting to Redford Barracks was conveniently only a 20 minutes walk from home, to which I was able to go that evening after an 8 month absence.

Two incidents in that brief association with Redford Barracks in the final week before release stick in the memory. One represented the army at its most intractable. Because the main strength of the Artillery unit based at Redford turned out to be on annual firing practice in west Wales, nobody left in Edinburgh would take responsibility for the sensible decision to hold us there until we reported to our Territorial unit for release five days later. So, the morning after my arrival in Edinburgh I was given another rail warrant to join the absent unit of artillerymen, encamped on a sodden former airfield where only duckboards kept feet above water. After a damp weekend of frustrated walking on a shingle beach for exercise, it took till Monday morning for anyone of seniority to issue a further rail warrant back to Edinburgh for a last week in uniform. However, at parade one morning in that final week with national servicemen at an earlier stage in their service, one made a disparaging comment about the army which drew the anger of the regular sergeant. The sergeant replied fiercely to say how much the army had meant to him in providing a home, sustenance and support for which he was supremely grateful. While the sergeant’s attitude may not have matched that of men enlisted not by their choice, his feeling expressed so strongly is still an impressive memory

.

On the 28 September I reported to the 278 Territorial Artillery unit at its base in Grindlay Street, Edinburgh, to hand in equipment not required over the four years of my required attachment to it. My Discharge book noted that my military conduct had been very good (failing to observe that I had allowed a failure of the guard of our temporary camp in the islands of Hong Kong ) and that I was “honest sober and reliable—-and should make a good NCO.”) With such a recommendation I left full-time service and started terminal leave of two weeks overlapping with a start to University life, an adjustment which in respects may have had difficulties unacknowledged at the time.

Four years later after half a dozen weekend exercises and four fortnight-long camps on the North York moors or back to Salisbury Plain, I received a final Certificate of Service which recorded that I was discharged on completion of all National Service engagement and also without ‘medals, clasps, decorations, mentions in dispatches, or any special acts of gallantry or distinguished conduct brought to notice’. No stain on my character, apparently, nor any evident mark of any notable kind in army records.

Wannop – Return to Hong Kong in 1990

I did not return to Hong Kong for forty years, and as the aircraft wheeled over to land on the old Kai Tak airstrip projecting into the bay, the huge physical change since 1950 was entirely evident. Around a sixfold growth of population had occurred since the level of about 1million when I had left in 1950, risen from the 500,00 to which it had declined during the Japanese occupation. To someone most familiar with British and West European cities, the array of tall commercial and residential towers replacing the modest heights of colonial Hong Kong seemed an almost horrific new living environment. Not that the higher buildings did not replace squalor still evident in the surviving part of the old Walled City, but the overbearing height and intense density of the new Hong Kong was almost frightening to someone even knowing Edinburgh tenements in their later days before their clearance in the 1960’s.

Yet, there was no graffiti or obvious signs of vandalism amongst the gargantuan residential filing-cabinets; no vandalised park benches or broken brick balustrades. Few litter baskets yet little lying litter. Plenty of paint, magic markers and aerosols in shops, but scarce sign of them used to disfigure (or enhance) walls or empty spaces. Why does France, a country of high European culture have paint sprayed on some of its finest Renaissance architecture, but largely unmarked urban surfaces remain in Hong Kong ? Why does Hong Kong with a population as large as Scotland’s suffer such few signs public vandalism ? What in Chinese culture precludes physical vandalism yet seems to perhaps more readily tolerate drugs, vice, corruption and gambling ?

Huge change had been brought about since 1950 with the vast increase of population. The funicular railway to the Peak had been wholly modernised but the summit was now cluttered with telecommunication masts, limiting accessibility. Although like San Francisco’s trams the Star Ferry was seemingly unchanged, the Kowloon railway station of 1950 had been obliterated. From a new station no longer adjoining the landing of the Star Ferry, trains on the now electrified line to Lo Wu ran beyond and through to Canton – or Guanzhou as it had become known.

At last I could visit the Walled City, like medieval Edinburgh with electric power and a water supply, albeit leaking down the walls. On Nathan Road, Manhattan had replaced colonial buildings with few rooflines left as would have been as in 1950. Most Chinese on the street would have no memory or even conception of the Nathan Road I had seen, nor of the Hong Kong of its days under the British.

Walled City Kowloon: Cross section

Wannop – Lo Wu 1990

Forty years after I had last travelled to Lo Wu, the electric line from Kowloon ran from a new and relocated station no longer allied to the Star Ferry landing. Long gone were steam trains and open trucks for Chinese on the lowest fares; all – not just the British and more prosperous Chinese – now sat in comfort in coaches. Of the former stations, only Taipo Market had been preserved – a quarter mile from a large new station where the restaurant served spaghetti bolognaise – and no chopsticks. No longer were women at the old stations selling strips of dried beef and chiclets from trays and handed through open carriage windows; the now electrified line and its architecture came all from an international rapid-transit model design manual. Nor was there any graffiti – utterly unlike the Paris RER, the New York subway or – increasingly – the London Underground.

The New Territories of predominantly paddyfields were now superimposed with highways, new towns, building sites, power lines, quarries, scrapyards and abandoned rural roads. Rice paddies now planted for vegetables, but Hakka women still planting and harvesting with their round disc hats rimmed with a black curtain ad a handkerchief covering their exposed crowns. As I walked at Hakku Wai, the old women at the gate of the handsome walled village – like a Flemish beguinage – chattered irritatedly when they saw me pass and moved beyond sight; the open door to the village shut without a hand being shown.

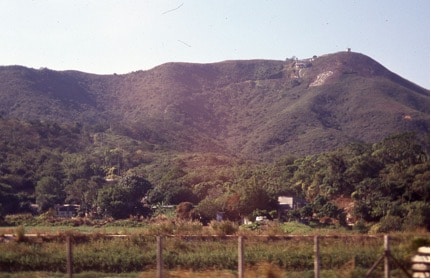

Crest Hill, Lo Wu 1990

Lo Wu had significantly changed. Although Hong Kong and the New Territories remained under British administration until 1997, the camp which the Royal Artillery had occupied in 1950 had now been succeeded by a detention centre for Vietnamese boat people who had escaped by sea to Hong Kong. From behind the barbed wire surrounding fence, screams and shouts came which were far less controlled than any of even an army camp.

I would have wished to climb Crest Hill again to look out over the great new city of Shenzhen prior to visiting over the border the next day. Warning signs of the Closed Zone and of a firing range dissuaded me. I chose not to be shot close to the Chinese border in 1990, having been at less risk of that fate as a soldier forty years before. The following day – with a visa readily obtained in Kowloon – I took the train to the border station of Lo Wu. I made the crossing into the People’s Republic impossible for me in 1950. Met by a Chinese Planner kindly arranged for me by a Chinese student of my department in Glasgow, I was given a day trip around the new urban landscape, wholly grown up in the decade since 1980 and forty years since my time at Lo Wu. A circle was closed on my experiences of National Service.

Recent Comments