Emerging from our tents at Lo Wu for our first morning parade on Feb. 27 1950, our welcome to China was by a lone Nationalist bomber of US origin flying in over the New Territories over our heads, dropping bombs over the border on the Chinese side in the vicinity of the railway line, close to a barracks of the People’s Republic Army. Its brief gesture over, the aircraft turned immediately to escape back to Formosa before the arrival of a flight of Spitfires from Kai Tak. For many years I thought that this might have been the last assault by the Kuomintang on mainland China – from which they had been largely expelled, only long after learning that three weeks later the Nationalists made a late fling in its long war with Mao and what had become the People’s Army, landing a force on the mainland coast north towards Shanghai.

South of Hong Kong, also in March, the People’s Army landed in greater force on the island of Hainan, driving out the occupying Nationalist troops by May. Nothing of the impact of these incursions was felt by us at Lo Wu, nor do I recall even learning that they had occurred. I have no memory any official briefing giving information about our position or that of Hong Kong in the changing Chinese world. Hong Kong’s security from any invasion across the border was in little doubt, because it was to the Chinese advantage to see out the life of the treaty legitimising British tenure of the New Territories. However, I had no fear of or expectation of any incursion by the People’s Army, although its troops were in view of our binoculars when we took observation duty from the top of our adjoining Crest Hill.

First morning on parade at Lo Wu, February 27 1950. Bomb strike by Kuomintang aircraft on Peoples’ Republic side of border.

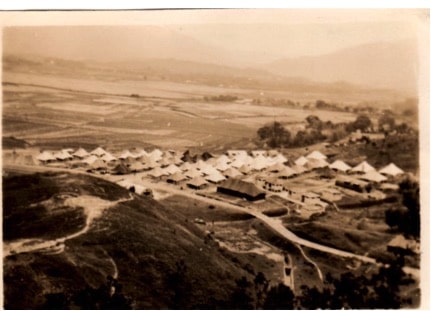

Lo Wu Camp 1950

Within the camp at Lo Wu there was a NAAFI hut and Chinese pedlars who came with unfamiliar confections like American Babe Ruth toffee bars. A Chinese concert party visited for one evening performance, but there were few other and only minor pleasures. No opportunity to again play hockey, but relief from the high humidity could be had by dipping in a storm balancing tank. Of an evening, we could stroll closer to the frontier and with villagers exchange a few grubby Hong Kong five or ten cent notes for souvenir currency of the Peoples’ Republic. There was no pleasure in a sweating climb up the zigzag path on Crest Hill for occasional overnight duty at the observation post overlooking China proper. Up the path, we carried full, top heavy jerry cans of water on frames on our backs, risking tumbling off the path as the weight of the water shifted in its container.

From the post itself, an ocean of paddy fields stretched to a line of hills on the horizon. Across this wide foreground of cultivated landscape ran the rail line from Kowloon to what then still known as Canton, far out of sight beyond a wall of hills paralleling that on which we stood in the New Territories. Then, no rail traffic crossed from the New Territories over the frontier, nor was there any complex of customs and visa control as I crossed through forty years later. The principal interest seen through field glasses was soldiers of the People’s Army sitting on the doorstep of their barracks by the rail line, perhaps the target of the bomber from Formosa of our first morning on parade at the Lo Wu camp.

We were innocent then of any foresight that the ocean of paddy fields before us would after 1980 be replaced by an industrial metropolis reaching an estimated population of 15 million within 30 years, outstripping the population and economic growth of Hong Kong and the New Territories. The Special Economic Zone established by metropolitan Shenzhen has become effectively the largest new town or city ever planned and built, more populous and larger in economic activity than achieved by all the new towns of the UK together in twice the lifetime. On my first subsequent visit to Hong Kong forty years later, it was fascinating for one who had come to a career as a town and regional planner – including a major period working on new towns in the UK – to return to a remembered landscape of paddy fields now overcome by the special economic zone of Shenzhen.

Guard duty at Lo Wu was ambling in the dark with rifles rather than the pickaxe handles of Larkhill, but not with matching ammunition. As we patrolled in the dark on two hour shifts, the night was heavy with the croaking of frogs from the paddy fields beyond the bamboos on the camp’s edge. In the still, humid and heavy night air, luminous caterpillars shone in the dark and trodden underfoot left a smear of fire.

Gunner Urlan Wannop, Lo Wu 1950

L to R. Gunners Pearson, Wallace and Wannop prior to guard duty Lo Wu 1950

Leave a Reply