I did not return to Hong Kong for forty years, and as the aircraft wheeled over to land on the old Kai Tak airstrip projecting into the bay, the huge physical change since 1950 was entirely evident. Around a sixfold growth of population had occurred since the level of about 1million when I had left in 1950, risen from the 500,00 to which it had declined during the Japanese occupation. To someone most familiar with British and West European cities, the array of tall commercial and residential towers replacing the modest heights of colonial Hong Kong seemed an almost horrific new living environment. Not that the higher buildings did not replace squalor still evident in the surviving part of the old Walled City, but the overbearing height and intense density of the new Hong Kong was almost frightening to someone even knowing Edinburgh tenements in their later days before their clearance in the 1960’s.

Yet, there was no graffiti or obvious signs of vandalism amongst the gargantuan residential filing-cabinets; no vandalised park benches or broken brick balustrades. Few litter baskets yet little lying litter. Plenty of paint, magic markers and aerosols in shops, but scarce sign of them used to disfigure (or enhance) walls or empty spaces. Why does France, a country of high European culture have paint sprayed on some of its finest Renaissance architecture, but largely unmarked urban surfaces remain in Hong Kong ? Why does Hong Kong with a population as large as Scotland’s suffer such few signs public vandalism ? What in Chinese culture precludes physical vandalism yet seems to perhaps more readily tolerate drugs, vice, corruption and gambling ?

Huge change had been brought about since 1950 with the vast increase of population. The funicular railway to the Peak had been wholly modernised but the summit was now cluttered with telecommunication masts, limiting accessibility. Although like San Francisco’s trams the Star Ferry was seemingly unchanged, the Kowloon railway station of 1950 had been obliterated. From a new station no longer adjoining the landing of the Star Ferry, trains on the now electrified line to Lo Wu ran beyond and through to Canton – or Guanzhou as it had become known.

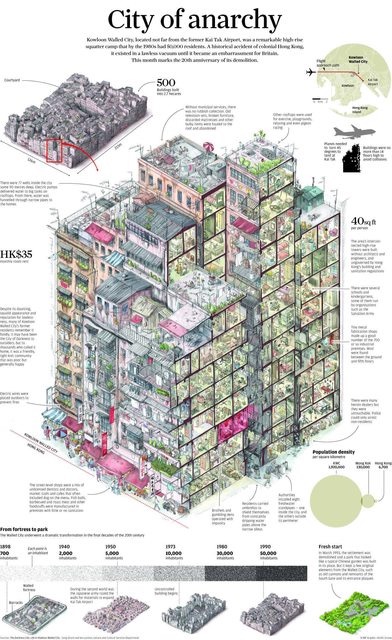

At last I could visit the Walled City, like medieval Edinburgh with electric power and a water supply, albeit leaking down the walls. On Nathan Road, Manhattan had replaced colonial buildings with few rooflines left as would have been as in 1950. Most Chinese on the street would have no memory or even conception of the Nathan Road I had seen, nor of the Hong Kong of its days under the British.

Walled City Kowloon: Cross section

Leave a Reply