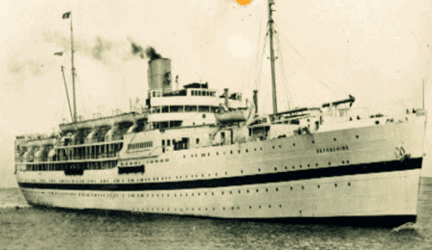

We sailed east on the 24 January 1950 from the Pierhead, from which emigrants had shipped west to North America fifty years before. Launched on the Clyde just ten years previously and fitted out as a troopship, conditions on the Devonshire seemed to us perhaps scarcely better than for those fifty years before sailing as emigrants to North America. Meals in bulk had to be carried down in containers from the galleys to the deck level where we lived, ate and slept. The food was no treat to receive; on the mess tables cleared of papers and clothing for meals we were presented with unappetising food of which pilchards in cold tomato sauce were particularly unappetising and wholly unsuited to anyone inexperienced in the rolling waves of the Bay of Biscay. Later on the voyage, however, oranges brought up from cold store were a rare pleasure after the barren days of food rationing still lingering in the UK.

Winter in the Bay of Biscay and even through the Mediterranean was not a season in which to much enjoy the shoreline landscape of Spain, or later of the Red Sea. It was possible, however, to go forward on the open deck to watch dolphins leap from the water and plunge ahead of the bow as it cut the water. Flying fish would follow the lead of the dolphins, darting above them at speed.

Our first direct contact with foreign parts came when briefly anchoring at Suez, when Egyptian traders paddled out in bumboats to sell sweets and souvenirs. Baskets on a rope were hauled up with the goods desired and returned back with money to the traders in the craft below. After sailing through the Suez Canal, the first shore leave came at Aden on Feb 8, bringing for most of us the first experience of placing foot on foreign soil. This all at a time before the days of mass flying to foreign holidays in the Mediterranean, the Maldives or other places then barely accessible except by sea. More brief release ashore came at Colombo a week later, followed by Singapore after passage through the Straits of Malacca. Hong Kong followed after a further five days through the South China Sea, completing a voyage from Liverpool of five weeks. There is still a picture in my mind of turning close around the rocky coast towards Hong Kong Bay. We moored by the Kowloon godowns, disembarking to board a steam train at the then Kowloon station, since displaced. We British troops had compartmented carriages to sit in, but many Chinese huddled in open trucks at the rear of the train. At the stations on the line, vendors brought trays of chewing gum and cuts of dried meat of origins unrecognisable to us.

The line to Canton being than closed at Lo Wu at the border with the new People’s Republic, the last open station on the line was Sheung Shui, from which we were trucked to the camp at Lo Wu where I spent most of the next six months. The almost wholly tented camp lay in the lee of Crest Hill in the line of hills separating us from the People’s Republic, declared by Mao in Beijing just four months before. My unit was the 15 Observation Battery; associated in residence in the camp with the 173 Locating Battery of the Royal Artillery.

Leave a Reply